Simon Eccles looks back across two decades of large-format inkjet print and highlights the main technical developments along the way.

The history of large-format over the 20 years Image Reports has been published hasn’t been a linear progression of technology, machinery and markets, but rather a lot of strands intertwining and driving each other. Applications and markets too, have shifted as new digital print technologies either opened up completely new possibilities, such as one-off, localised/personalised or short run items. New technologies have also prompted a partial transfer in technologies from long-run analogue to short-run digital, notably from screen to durable inkjet for outdoor sign and display, from screen, offset and electrostatic for indoor sign and display, from screen, offset and earlier digital processes such as dye sublimation for fine art and photographic applications.

Simultaneously with printer developments, huge strides have made in inkjet printheads, inks, media, computing power and software.

Printers themselves have been built to serve parallel markets that don't always overlap. There’s the high quality photo/poster/fine art market; then the indoor point-of-sale, display and wall panels market, then pop- ups and exhibition work, then outdoor banners, signage, and vehicle graphics. Textiles are of growing importance, for clothing and furnishings as well as wall hangings and soft signage.

Early inkjets

The first larger format inkjets to make much impression on the market were made by Iris in the USA from the late 1980s. These were used for photographic, fine art and proofing applications. Iris was acquired by Scitex in 1992 and after that the proofing side predominated.

Digitally driven printers for larger formats were largely confined to £100,000 44in liquid toner electrostatic models from Versatec, which was subsequently acquired by Xerox Engineering Systems. Harry Bowers at Cactus Imaging

and Ron L Jones at Colossal Graphics in the US did a lot to turn these early CAD-oriented printers into poster printers, according to Jeff Biggs at Colourgen. Jones commissioned the PowerScript Rip to process graphic arts files, while Cactus adopted High Saturation Graphics Toners from Specialty Toner Corporation.

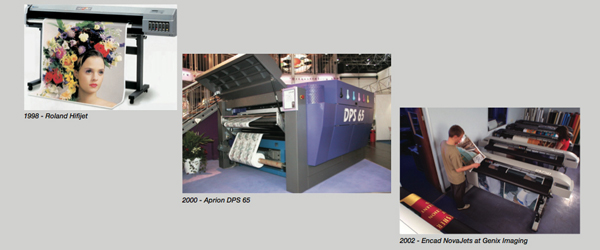

In 1992 Encad in the US developed the NovaJet,probably the first wide-format inkjet with a modern configuration of drop-on-demand heads. Colourgen was the UK agent. This used HP heads and water based inks intended for CAD use, driven by the PowerScript Rip for poster work. It was very slow but only cost about £30,000. Subsequent models were faster and saw the introduction of bulk ink feeding, a more suitable ink developed by Lyson and then in 1996, a 50in wide model, the NovaJet Pro 50. By 2000 Encad was facing a lot more competition and in 2003 Kodak bought the company. It intended to introduce new models, but technical issues saw Kodak lose interest and move out of wide-format.

The late 1990s saw Epson and HP introduce their first-wide format models above 24ins. These all used water-based inks at first, though Epson sold its micropiezo heads to other manufacturers that did use them for solvent and other ink types. Only comparatively recently has Epson started making its own light solvent printers running its GS and GS2 ink sets, and then more recently still, dye sublimation textile printers.

Today’s Epson Micropiezo Thin Film Piezo printhead technology is a direct descendent of technology it developed in the 1990s, and can be spotted by the 360/720dpi native resolutions. This year the company introduced the PrecisionCore head family, with new MicroTFP technology using allowing finer nozzles and 600dpi native resolution. This is being used first in a narrow web UV label printer, but will be rolled out into future large-format printers.

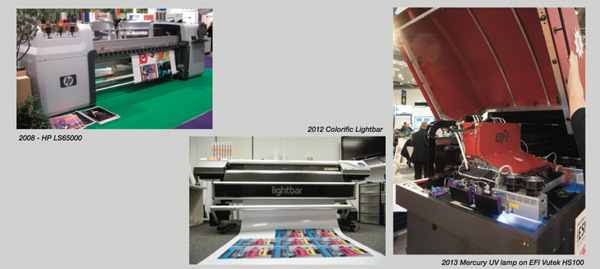

Hewlett-Packard, before it preferred to be called just HP, invented the thermal inkjet printhead in the mid- 1970s, independently but at around the same time as Canon made much the same invention in Japan. HP’s core competence remains thermal in every niche from cheapo home desktops through to heavy-duty office printers, wide-format aqueous ink (mostly called Designjets) and even the massive T-series commercial inkjet web presses. The water-based latex ink, apart from its greenery aspects, also allows HP to use its thermal head technology in outdoor wide-format applications.

Where it’s using UV and solvent inks in wide-format today, you’ll find that their originals are bought-in companies or systems that of necessity use piezo (ie non-thermal) heads. HP’s industrial print range is mostly developed out of acquisitions it made in the 2000s, most notably Scitex Vision, which is the basis of today’s HP Scitex.

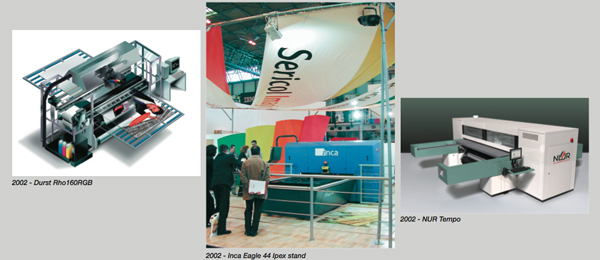

Israel in the 1990s saw the foundation of a number of grand or superwide printer manufacturers, including Idanit, NUR Macroprinters and later on, Aprion, which developed its own piezo printheads and some innovative printers for on-demand books, wall coverings and corrugated packaging. Most ended up as part of the Scitex Wide Format Printing operation that was later renamed Scitex Vision before being taken over by HP in 2005 and renamed HP Scitex. NUR remained independent until 2008, when HP bought it too. Matan built early large and grand format printers for NUR and Scitex, but remained independent and today sells printers called Uvijet via Fujifilm.

Canon was producing good small format photographic inkjets in the 1990s, but it took several more years before it entered into wide-format with its imagePrograf family from 2004 onwards. These remain water-based, but Canon’s acquisition of Océ has gained it the Arizona range of UV flatbeds and the ColorWave models with CrystalPoint solid ink technology.

Brits fly the flag

The UK can also hold its head high, with a surprisingly large number of printhead and printer developers and manufacturers, many of which trace their origins back to the various colleges of Cambridge University and

its commercial spin-offs, particularly Cambridge Consultants Ltd (CCL). In particular these include Domino Printing Sciences, Elmjet, Inca Digital and Xaar. Xennia and Industrial Inkjet aren’t CCL spin-offs but also have a good track record of innovation. Sericol (now Fujifilm Speciality Inks), SunJet and Lyson (now part of Nazdar) are all UK based ink manufacturer of global importance.

In 2007 Image Reports carried a story tracing the early development of inkjet in the UK, USA and Japan, to mark the retirement of Xaar’s technical director Stephen Temple, who together with colleague David Paton had laid a lot of the groundwork for piezo printhead development in the 1970s and 80s at Cambridge Consultants. They left to found Xaar with help from venture capital in 1990. The full story is still online.

Xaar’s piezo printheads are widely used in industrial inkjets, and the technology has been licensed by other manufacturers, notably Toshiba-Tec , Konica Minolta and Seiko in Japan. Stockwatchers will have noticed that Xaar’s share price has quadrupled in the past 12 months, due to healthy sales into the ceramic tile printing sector, particularly in China.

Ripping yarns

Advances in Rips and other print-related software have been more important to print users than developments in the hardware platforms that ran them. The 20 years has seen the introduction of more and more automation, including intelligent ganging/nesting, pre-flighting and colour management (always important in proofing and fine art/photography, but only just impacting on signage as brands make their requirements increasingly clearer).

One of the first specialist large-format Rip developers, Onyx, is still around today having changed hands a couple of time and is now under the Canon/Océ wing. EFI was building Fiery servers for Canon copiers in 1994, but by the end of the 90s had introduced software Rips for large-format devices. EFI also took over the Best large-format proofing Rip in 2004 and incorporated its technology. Applied Image Technology (with Shiraz), Wasatch and ColorGate are all names from the early days of wide-format Rips that are still around today. The French Caldera Rip is currently particularly well thought of as a third party choice.

Cloud-based services will undoubtedly start to impact printing software. An early example is SAI’s latest PhotoPrint Cloud, a large-format Rip workflow that offloads a few functions to remote services, including fast job quoting and reporting, and media profile updates.

Printheads and inks

Most of the relevant developments in printheads have been for drop-on-demand types, and within that category a lot of the action has been in piezo-electric types, which can handle a much wider range of fluids than thermal heads that are confined to water-based inks. Continuous flow inkjets were used in early fine art (‘giclée’) and proofing printers including the Iris and Du Pont Digital Cromalin systems, but by the early 2000s these had been almost completely replaced by drop-on- demand heads.

Inks themselves have gone through huge technical developments since 1994, and these deserve equal coverage with the printers and heads. At the start of Image Reports’ run the choice was pretty well confined to water-based fluids with dye colorants. These had little outdoor durability without lamination, and faded fast, though that was cured by later pigment-dye compounds. Oil-based inks were also used in early inkjets, being waterproof and fairly durable, but at a distance of 20 years we’ve found nobody with any nostalgic enthusiasm for them.

Two development efforts led to some of the most important outdoor inks we have today. Solvent-based inks, already in use for screen process, were formulated to work within the much tighter constraints of inkjet nozzles. Solvents key themselves and their colorants into the top layer of plastic media, forming a permanent, weatherproof and fade resistant bond.

Volatile solvents won’t work in thermal inkjet heads, so they were dependent on the introduction of cool running piezo heads from the likes of UK based Xaar (which licensed its technology widely, especially in Japan) and US based Spectra (which became Dimatix before being acquired by Fujifilm in 2006).

The original ‘strong solvent’ inks were hazardous to operators, so needed forced ventilation during printing and remained unpleasantly smelly afterwards so weren’t suited to indoor use. By the early 2000s ink companies, including the UK’s Lyson in Stockport, were developing ‘light solvent’ inks whose health rating was merely ‘irritant’ rather than ‘hazardous’, and they had little residual smell. Originally they weren’t as weatherproof or brightly coloured as strong solvents, but manufacturers have progressively improved them in the past ten years.

It was Lyson that also developed the first eco- solvent version of the Roland inkjets, according to John De La Roche

and Mat Drake, who worked for Roland in the 1990s (Drake is still there and De La Roche is now at Hybrid Services). Roland had developed pen plotters in the 1980s that sold to plan and map makers, and in 1995 it put a cutting knife in place of the pen to form an early vinyl cutter. Meanwhile it also developed a range of aqueous ink large-format printers including the HifiJet, used for proofing and photo printing. Because these used Epson micropiezo heads, they were suitable for conversion to more volatile solvent inks.

Mutoh and Mimaki, two other Japanese inkjet manufacturers founded in the 1990s that play a major part in today’s market, also developed inkjets based on Epson heads and a wide range of ink types, though they sourced heads elsewhere too.

UV curing is another outdoor durable ink technology that originated in offset and screen processes. Early users of UV inks include Vutek from the US, with its UltraVu models, and Inca Digital from the UK, with its Eagle 44 very high speed flatbed launched at Ipex 2002. Now the use is widespread in a wide choice of manufacturers and configurations.

UV inks were originally thick and rigid so they’d crack off anything that flexed too much. Over the years printhead drop control has grown more sophisticated and ink formulations have been refined, to the point that they’re now suited to far more flexible media, such as banners, vehicle curtain sides and (up to a point) vehicle wraps.

An interesting development of the past couple of years has been solvent-UV hybrid ink for plastic media, currently available from Mimaki in its JV400SUV 1.3 and 1.6m printers, and from Colorific as part of an aftermarket conversion set for a growing number of Mimaki, Mutoh and Roland printers. Here a small amount of solvent in the ink keys it into the surface of plastic media and is rapidly evaporated by heaters on the printer, while the main UV-sensitive component is cured by a downstream UV lamp array. The result is claimed to be thinner and more flexible than normal UV, with great adhesion and scratch resistance, for sensible costs.

In 2008 HP announced Latex, an outdoor-durable ink technology that has an aqueous base, so it works with the company’s thermal printheads. Early in 2013 Mimaki started shipping a Latex aqueous-base ink of its own, in the JV400LX (which uses Ricoh piezo heads). Ricoh will also sell a version of the same printer under its own label. However, Mimaki anticipates greater sales of its solvent-UV hybrid ink version of the same model.

Compressed history

This has been a brief scamper through 20 years of enormous change in the printing industry, its technologies and the markets it serves so the piece has necessarily kept to broad trends with only a few specific companies, machines and people mentioned as highlights. Many more have contributed to where we are now, but full coverage would fill a book or two: 20 years of Image Reports’ own coverage is rather more words than ‘War and Peace’.

However, plenty of people have given generously of their time in preparing this story, reminding me of key events, people or systems. Particular thanks go to Jeff Biggs and Melanie Ensor at Colourgen; John De La Roche at Hybrid Services; Mat Drake at Roland DG UK; Martin Johns at Epson UK; Sophie Matthews-Paul at Rockstro; and Michael Reidy at The Bespoke Agency.

{jathumbnail off}